Our faculty in the Education Department at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte often spends time discussing issues we see within our middle grades program, including with our undergraduate teacher candidates in clinical and student teaching settings, with practicing teachers in initial licensure programs, and those learning their way into an M.Ed. in Middle Grades Education. It was at one such meeting that we found ourselves returning to the concern of our content area teachers not feeling knowledgeable about working with Latino newcomers. We were talking our way around the edges of the topic, hoping for solid language that would give clear voice to this issue, when Jeanneine shared

this story:

I’d never encountered a child who truly couldn’t speak a single word of my own language. Yet there they were, two gorgeous Latina girls sitting quietly in the very back of the room, hands folded, staring at the tree outside the window, surely bored half to death, understanding absolutely nothing. The teacher wasn’t helping much either because, just like me, she didn’t know what to do or even where to begin. She didn’t speak their language, and they didn’t speak hers. Much to my dismay she made a beeline straight for me after class, and I was pretty sure it wasn’t to discuss the student teacher I’d come to observe next block. Instead, just as I feared, it was to eagerly ask for my advice on how to work with those two girls. My conversation on the topic was short, with that five minutes pretty much covering everything I knew. That day left a real mark on me. That image, though 20 years old, is still so vivid in my head that I can recall the yellow shirt one of the girls was wearing. Like I said, it left a mark on me because it forced me to confront something that was a dangerous void in my teacher life, and I realized I’d better figure it out fast. I’m worried that our program still isn’t where it should be in this area, and especially given our growing Charlotte Latina population.

Jeanneine later shared that things got better for the two Latina girls with the arrival that semester of an English as a second language educator. This teacher helped them on their way to learning a new culture, navigating a new school, and, even more important, becoming a part of the school community through both curricular and extracurricular activities. In time, the language became easier for them, too, opening not only academic doors but social windows, which are critically important to young adolescents (Strahan, L’Esperance, & Van Hoose, 2009; Stevenson, 1998).

Twenty years later, thousands of young adolescents now come into our middle grades classrooms from a rich array of countries, some with a strong working knowledge of English, some with emerging proficiency in their new language, and some with nothing at all in terms of mainstream communication skills—many, like those two young girls, are of Latino heritage.

Culture plays a critical role in the most effective middle schools (NMSA, 2010), and we consider transnational children of immigration to be a great wealth, a rich blessing. We work tirelessly to equip today’s middle grades teachers to serve this group of children better than we did 20 years ago. As teacher educators within The University of North Carolina Charlotte’s large, urban college of education, we now regularly receive requests for assistance from middle and high school teachers and administrators who are interested in establishing a better school environment for their increasingly diverse adolescent populations. In central Piedmont, a large and growing number of Latino families accounts for much of that diversity.

As of 2007, Latinos comprised 15% of the total U.S. population, with approximately one-third self-identifying as Mexican in origin. In North Carolina, the percentage of Latinos has increased by approximately 69% from the years 2000 to 2007 (National Council of La Raza, 2010), and they continue to transform communities across the state in wonderful and dynamic ways. Unfortunately, though Latino schoolchildren are the fastest growing K–12 population in the U.S., their educational achievement in the middle grades remains significantly lower than their non-Latino counterparts across disciplines.

While recognizing that measures of school achievement are generally social constructs that can marginalize non-dominant communities, these measures must be considered, nonetheless, as they have become a critical part of conventional school conversation. As with all groups of children, Latino achievement matters for the futures of these very same families and for our nation’s place in the global workforce. Addressing the educational needs of immigrant and U.S.-born Latinos in the middle grades can help curtail a cycle of underperformance indicative of past generations.

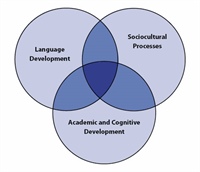

Figure 1

Making schools work for Latino adolescents (cf. Collier, 1996)

Although professionals across many fields need to consider the multiple and overlapping domains at play in the educational development of children of immigration (see Figure 1), our focus is specific to the sociocultural processes at work in classrooms and schools. These processes include “the social and psychological distance between first and second language speakers, perceptions of each group in interethnic relations, cultural stereotyping, intergroup hostility, subordinate status of a minority group in a given region, and patterns of assimilation” (Collier, 1998, p. 21).

Teacher education for the middle grades must embrace the culturally and linguistically complex spaces that our classrooms and institutions have become. In particular, we need to better develop our individual and collective dispositions—attitudes about difference that can play an enormous role in the achievement of youth from non-dominant communities.

Latinos in the middle grades are particularly vulnerable to potentially harmful sociocultural processes at work in classrooms, curricula, and institutions. In their large-scale longitudinal study of immigrant children’s adaptation processes, Suárez-Orozco and Suárez-Orozco (2001) documented the extent to which immigrant adolescents are susceptible to toxic social mirroring about their potential and self-worth (see also Portes & Salas, 2010). Because middle grades teachers are educated specifically to work with early adolescents, and because they hold the collective wisdom that comes from teaming (NMSA, 2010; Powell, 2011; Strahan, L’Esperance, & Van Hoose, 2009), those who educate this age group are uniquely positioned to counteract institutional and community messages that may stereotype Latino adolescents in negative ways. Even more important, middle grades teachers who form positive relationships with Latino youth can make a difference in their educational trajectories, or as the Association for Middle Level Education (AMLE, formerly NMSA) (NMSA, 2010) has articulated, “Academic success and personal growth increase markedly when young adolescents’ affective needs are met. Each student must have one adult to support that student’s academic and personal development.” With Curtin (2006), we find that the positive effects of such advocacy are especially apparent for young Latinos who work better for teachers whom they feel care deeply about them and about their futures (see also, Valenzuela, 1999). Caring, we argue, begins with talking.

Let’s talk

Middle grades teams often pose very appropriate questions that range from “What motivates Latino students?” to “How can I better engage immigrant parents?” However, they generally ask these questions of each other, the school’s ESL teacher, their university professors, or search the literature that they study about immigrant children. Although these are very useful approaches, the most powerful tool middle grades educators can employ is direct conversation with their students; for example: “Who are you as a Latino?” “What does that mean to you?” “How is your culture different from the cultures of other adolescents in our class?” “In what ways is it the same?” In other words, rather than talking generally about Latinos, who they are, and what distinguishes them from other adolescents, we should ask our students directly how schools might work better for them and their families, in particular. Begin that association in an authentic and meaningful way through simple conversation:

Habla con ellos. It is through talking to our students that we help them form healthy personal identities and positive relationships with peers and adults (Strahan, et al., 2009). Three initial questions work well to open the conversation: “Tell me about your family,” “I love that we are different, but how are we the same?” and “What do you do best, and what brings out the best in you?”

“Tell me about your family”

Though we talk to our students about who they are, we rarely take time to ask about their families; this, in turn, can quickly lead to assumptions and stereotypes regarding an immigrant students’ familial and cultural history. For example, many educators we work with are surprised to learn that the majority of Latino English language learners (ELL) in K–12 schools were actually born in the United States and have attended U.S. schools all of their lives (Passel, 2009). A teacher’s inadvertent framing of a U.S.-born Latino as “not American” might perpetuate a sense of foreignness. Acknowledging and engaging the complex ethnic identities of students is essential to affirming the cultural mosaic of our middle school classrooms, our local communities, and our nation (NMSA, 2010). It all begins with simply saying to your students, “Tell me about your family.”

Let’s take a look at how that plays out in a classroom: Janet is an eighth grade social studies teacher in a rural North Carolina middle school. Many of her students are from Puebla, Mexico. On any given day, you can walk into her class and hear adolescents conversing in both English and Spanish. She encourages her students of both Mexican and United States heritage to collaborate. Code-switching—effortlessly shifting between Spanish and English in a single communicative event—is just one way the students leverage their linguistic dexterity to collaboratively navigate the social studies curriculum.

As part of this state-mandated curriculum, Janet is responsible for teaching her students about the various industries that have called their state home. As she got to know her students, she came to realize that many of their parents worked in the local chicken processing plant. Since food processing stands as an important state industry, she decided to assign her class the task of interviewing their parents, other plant employees, and community members to determine how the plant has interacted with their lives, the surrounding community, and North Carolina in general.

At the assignment’s end, the students were excited to share their findings, and a rich conversation permeated the room for days through both academic dialogue and social conversation. Mexican students discussed the layers of their transnational identity and how moving from a large city like Puebla to a small rural community was a cultural shock. Others explained how their parents came to the United States years before they were even born and that their cultural experiences have been primarily through the eyes of their parents and older family members. European American and African American students realized that their previously held misconceptions of life in Mexico (i.e., sleepy villages, cacti, and undocumented immigrants who sneak across the border in the dead of night) were incongruous to the rich, multifaceted, charismatic life experiences of their classmates. In addition, the class enjoyed a detailed discussion that focused on the chicken processing plant, the labor conditions that their family members experienced there, and the role of this large industry in shaping the community’s culture. As the students’ final discussions and project presentations came to a close, Janet again emphasized their experiences as members of the community, of the school, and of their families; the role of globalization in industry; and how various cultural values shape contemporary North Carolina life.

Honoring the cultural histories of immigrant adolescents means taking an engaging approach to curriculum by developing instruction that reaffirms Latino students’ “funds of knowledge” or their ways of knowing that students learn at home and in their communities and bring with them to school (Moll et al., 1992). This volitional change in mindset shifts teachers from deficit thinking (i.e., what my students don’t bring to school) to a culturally responsive disposition (i.e., what my students contribute to the learning) that, instead, centers on a concept of “gifts” students offer. Geneva Gay (2000) refers to culturally-responsive teaching as “using the cultural knowledge, prior experiences, frames of references, and performance styles of students from diverse backgrounds to make learning environments more relevant to and effective for them … (which is) culturally validating and affirming” (p. 2). Middle grades teachers who leverage Latino students’ unique familial and cultural histories into their instructional design will not only motivate learners within their classrooms but will also foster a sense of engagement that can translate into higher achievement.

“I love that we are different, but how are we the same?”

We acknowledge and celebrate diversity in our classrooms. However, talk of diversity often focuses on the differences between us. Though we want to avoid downplaying adolescents’ distinct cultural histories and individual uniqueness, we can also address the many commonalities we share. According to Schumann’s Acculturation Theory (1998), second language acquisition parallels second culture acquisition. An important component of this theory is the notion of social distance or the degree of difference between cultures. Learners who feel that the culture of the second language community is very different from their home culture may struggle to adjust to and become comfortable in environments in which they are framed as outsiders. So, if we strictly emphasize how Latino and non-Latino cultures are different, we may inadvertently exaggerate social distance and impede our Latino students’ academic progress.

Social isolation is sometimes apparent in middle grades classrooms in which teachers might observe Latino students hanging out exclusively with fellow Latinos. To facilitate interaction between Latino and non-Latino students, teachers will likely need to engage them in dialogue about what they have in common, regardless of ethnicity or national origin. That dialogue can quickly begin by asking our Latino and non-Latino students how we are unique and how we are similar.

For example, in Rowan County, North Carolina, Luis leveraged his role as the school’s soccer coach to create a mentoring program in which seventh and eighth grade Latino and non-Latino athletes began each practice with a focused conversation about things going on at school and in their lives. At the start of the season, they generated a list of issues they wanted to address in their discussions. Luis then began each practice by facilitating a short, open-ended conversation based on these topics; topics included his players’ relationships within the school, bullying, dating, and a variety of social situations that seemed common across the group. The season later concluded with a shared reading of A Home on the Field (Cuadros, 2006)—the story of how a soccer team’s rise to the state championship recast a small North Carolina town’s secondary school’s relationship with its Latino community. In the case of Luis and his student athletes, conversations brought them closer together by creating a space where they could talk about the things that mattered to them at that moment. More often than not, the boys found that they did have much in common with their teammates. Soccer practice became a focused time for honing individual and team skills to succeed on and off the field, with the strong message that we can do more if we understand and support each other.

“What do you do best, and what brings out the best in you?”

Working better for and with Latinos and other students might begin by teachers asking, “What do you like to do?” or perhaps “What are you good at doing?” Institutional understandings of Latino adolescents’ potential and achievement are often framed in the idea that decisions governing retention, promotion, and graduation should be based on a single, high-stakes, standardized test score—what Valenzuela (2004) calls “Texas style accountability.” Unfortunately, too many of our Latino students may not see a relationship between what they do best and what we ask of them in our assessments. In addition, they may have heard about what they’re not good at doing for so long that they have actually internalized the idea that they aren’t particularly good at doing anything at all—or at least not anything that schools value. The category of English learner is one such example; the thing that many Latino children are good at doing, being bilingual, is often undervalued and ignored rather than called on and celebrated. Though we may be weary of stereotypes that unintentionally limit educators’ expectations, we can generalize that Latino children of immigrant families have indeed developed strategies for adapting to new communities and circumstances. For example, when facing crises Latino families can mobilize their communities quickly through reciprocal networks (Suárez-Orozco & Páez, 2002). What’s more, in terms of their expectations for teachers, Latino parents generally focus on the “educación” of their children, or the manner in which they are expected, from a Latino perspective, to interact with others (Rodríguez-Brown, 2010; Valdés, 1996).

Cultivating the kind of classroom environment in which teachers and students talk to each other about what they do best and what brings out the best in them takes time. Many students have likely never been asked such a question by a teacher, or at least not with frequency. Should middle school teachers find that engaging students in that sort of dialogue is too difficult, they can turn to the families of their students by including them in a discussion about experiences the family has had with schools, administrators, and teachers. Should those conversations include negative situations, teachers can also ask how those experiences could become more positive for the family. In this way, we all learn from each other.

Again, let’s turn to the classroom for a tangible example: In his culturally and linguistically complex eighth grade social studies classroom in Cabarrus County, North Carolina, Jeff was so inspired by his students’ freehand cartooning and doodling that he introduced cartooning software into his curriculum. Students who had readily described history as boring and who perceived themselves as disinterested and even struggling students were immediately absorbed in story boarding historical events, such as the French Revolution, and historical concepts, such as citizenship and freedom. Because story boarding requires the framing of text with images across cartoon-like cells, Jeff quickly recognized its connection to more sophisticated graphic novels, and he decided to use these novels as alternatives to his history textbook (Christensen, 2006). Allowing for additional layers of critical analysis, and after providing language scaffolding for the English language learners (Frey & Fisher, 2004), Jeff passed out copies of A People’s History of American Empire (Zinn, Buhle, & Konopacki, 2008). Embedded with pictures, the graphic text offered students visual renderings of complex social studies concepts and served as an engaging ancillary to his daily instruction. As a culminating project, the students developed their own graphic short stories on the history of democracy. Through cartoons and graphic novels, Jeff found a way of simultaneously building his students’ competencies in technology, content understanding, collaborative learning, and innovative thinking about social studies. Moreover, he deeply interested them in the content of the class, and, as a result, the majority of his students began thriving.

Habla con ellos

Contemporary teacher education and professional development for the middle grades and elsewhere continues to fall short for many transnational children of immigration. Instead of shying away from our individual and collective shortcomings, we can embrace what we don’t know as a starting point for professional renewal—just as our colleague, Jeanneine, shared in the vignette that opened this discussion. Professional renewal can begin with a conversation. Talk to them. Who students are, where they come from, what they already know and know how to do, and who they are in the process of becoming are all engaging relationship builders. These topics can and should serve as starting points for dialogue and community growth in each middle grades classroom. This is doubly important for our Latino newcomers, who have so much to offer beyond the stereotypes with which they are often labeled.

We have discussed three initial questions that are guaranteed to grow meaningful and strategic discussion in middle grades classrooms: “Tell me about your family,” ” I love that we are different, but how are we the same?” and “What do you do best and what brings out the best in you?” There are, of course, endless others. More dialogue is necessary across K–12 institutions, but such dialogue is especially urgent for developing young adolescents across the middle grades. As Wang and Holcombe (2010) have argued, adolescents’ perceptions of their middle grades environment directly and indirectly influence their academic achievement. We must, therefore, work with Latinos to make schools and schooling more welcoming for them. We need to consider not only the risks and challenges of these critical years but also what makes middle grades students succeed. This process can begin by “identifying and nurturing young people’s ‘sparks,’ giving them ‘voice,’ and providing the relationships and opportunities that reinforce and nourish thriving” (Scales, Benson, & Roehlkepartain, 2011, p. 263).

The questions we have composed here could very well engage all students across the middle grades, and we hope educators will continue to work to create spaces for dialogue with as many students as possible. Latino adolescents especially need strong advocates during these middle grades years, a critical juncture in their personal and educational trajectories. We know that nationally Latino adolescents are not thriving in the middle grades, but many educators want to make a difference, a big difference. They want to know the answers to “What motivates Latino students?” and “How can I better engage immigrant parents?” These questions require a commitment to knowing our students better and to communicating that middle grades education is a participatory, additive, and nourishing process grounded in solid relationships and ongoing dialogue. Habla con ellos—Talk to them.

References

Christensen, L. L. (2006). Graphic global conflict: Graphic novels in the social studies classroom. The Social Studies, 97, 227–230. Collier, V. P. (1998).

Promoting academic success for ESL students: Understanding second language acquisition for school. Woodside, NY: New Jersey Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages – Bilingual Educators/Bastos Books

Cuadros P. A. (2006). Home on the field: How one championship team inspires hope for the revival of small town America. New York, NY: Rayo.

Curtin, E. (2006). Lessons on effective teaching from middle school ESL students. Middle School Journal, 37(3) 38–45.

Frey, N., & Fisher, D. (2004). Using graphic novels, anime, and the internet in an urban high school. The English Journal, 93(3), 19–25.

Gay, G. (2000). Culturally responsive teaching: Theory, research, and practice. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Moll, L. C., Amanti, C., Neff, D., & González, N. (1992). Funds of knowledge for teaching: Using a qualitative approach to connect homes and communities. Theory into Practice, 31, 132–140.

National Council of La Raza. (2010). North Carolina state fact sheet. Washington, DC: Author.

National Middle School Association. (2010). This we believe: Keys to educating young adolescents. Westerville, OH: Author.

Passel, J. (2009). A portrait of unauthorized immigrants in the United States. Washington, DC: Pew Hispanic Center.

Portes, P. R., & Salas, S. (2010). In the shadow of Stone Mountain: Identity development, structured inequality, and the education of Spanish-speaking children. Bilingual Research Journal, 33(2), 241-248.

Powell, S. D. (2011). Teachers’ Days, Delights, and Dilemmas: Wayside Teaching. Middle School Journal, 42(3), 55-56.

Rodríguez-Brown, F. V. (2010). Latino families. In E. G. Murillo Jr.,S. Villenas, R. Trinidad Galván, J. Sánchez Muñoz, C. Martinez, & M. Machado-Casas (Eds.), Handbook of Latinos and education: Theory, research, and practice (pp. 350–360). New York, NY: Routledge.

Scales, P., Benson, P., & Roehlkepartain, E. (2011). Adolescent thriving: The role of sparks, relationships, and empowerment. Journal of Youth & Adolescence, 40, 263–277.

Schumann, J. (1998). The neurobiology of affect in language. Oxford, England: Blackwell.

Strahan, D., L’Esperance, M., & Van Hoose, J. (2009). Promoting harmony: Young adolescent development and classroom practices, 3rd ed. Westerville, OH: National Middle School Association.

Stevenson, C. (1998). Teaching ten to fourteen year olds, 2nd ed. New York, NY: Addison Wesley Longman.

Suárez-Orozco, C., & Suárez-Orozco, M. (2001). Children of immigration. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Suárez-Orozco, M. M., & Páez, M. (2002). Latinos: Remaking America. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Valdes, G. (1996). Con respecto: Bridging the distances between culturally diverse families and school: An ethnographic portrait. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Valenzuela, A. (1999). Subtractive schooling: U.S.-Mexican youth and the politics of caring. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Valenzuela, A. (2004). Leaving children behind: Why Texas-style accountability fails Latino youth. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Wang, M. T., & Holcombe, R. (2010). Adolescents’ perceptions of school environment, engagement, and academic achievement in middle school. American Educational Research Journal, 47, 633–662.

Zine, H., Buhle, P., & Konopacki, M. (2008). A people’s history of American empire. New York, NY: Metropolitan Books.

Spencer Salas is an associate professor in the Department of Middle, Secondary, and K–12 Education at The University of North Carolina at Charlotte. E-mail: ssalas@uncc.edu

Jeanneine P. Jones is a professor in the Department of Middle, Secondary, and K–12 Education at The University of North Carolina at Charlotte. E-mail: jpjones@uncc.edu

Theresa Perez is Professor Emeritus of the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. E-mail: tperez@uncc.edu

Paul G. Fitchett is an assistant professor in the Department of Middle, Secondary, and K–12 Education at The University of North Carolina at Charlotte. E-mail: pfitchet@uncc.edu

Scott Kissau is an associate professor in the Department of Middle, Secondary, and K–12 Education at The University of North Carolina at Charlotte. E-mail: spkissau@uncc.edu

Published in Middle School Journal, September 2013.

As we look more deeply into the needs of all of our students, this idea of communication is inspiring. May we all find ways to communicate better with our students and one another. Thank you for sharing this important work!!!