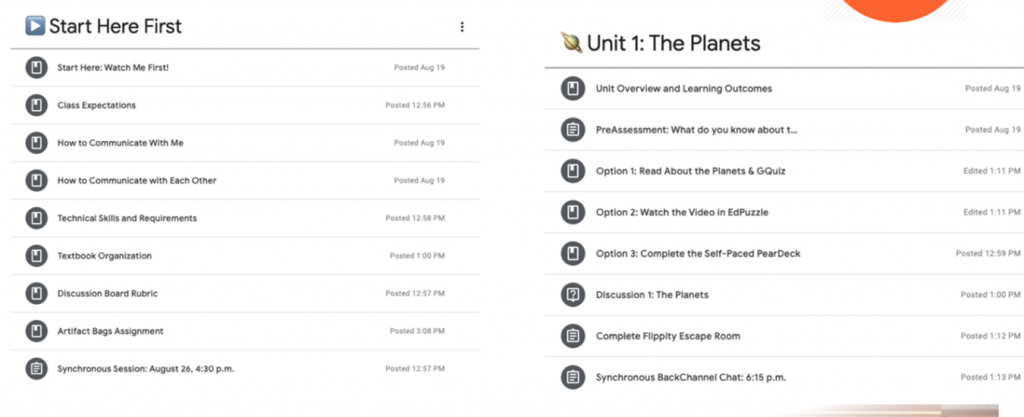

Take a minute and study the following image from an online course. Let’s start with a “notice and wonder” thinking routine. What do you notice (just the facts, please!)? What does this image (or those facts) make you wonder about (what interpretations do you have)?

The things I see are multiple formats of interaction (video, text, audio, PowerPoints), communication tips, layout explanations, and a paced-out unit of instruction. Some things I start to wonder about are how does a digital escape room work and how is the teacher evaluating the activities students are completing.

What you just noticed and wondered about is a model e-learning Google classroom. This model classroom is based on research that has empirically confirmed that participants can learn up to five times more material in an online course than a traditional face-to-face-course (Means, Toyama, Murphy, Bakia & Jones, 2010) and an MIT study that shows that online learning can be as effective as a traditional course regardless of how much preparation and knowledge students start with (Colvin, Champaign, Liu, Zhou, Fredericks, & Pritchard, 2014). It is also confirmed by preliminary data in another study that used the principles in this model to support student acquisition of content to high levels, levels that were parallel to local common assessment data of previous cohorts in multiple different districts.

So, what makes for this success? The answer is not in the organizational systems or communication systems in place (although these can help). The answer lies in three pedagogical reasons:

- Determining an aligned pedagogical purpose

- Connecting the technological apps to the pedagogical purpose

- Making student thinking visible in order capitalize on the formative assessment cycle

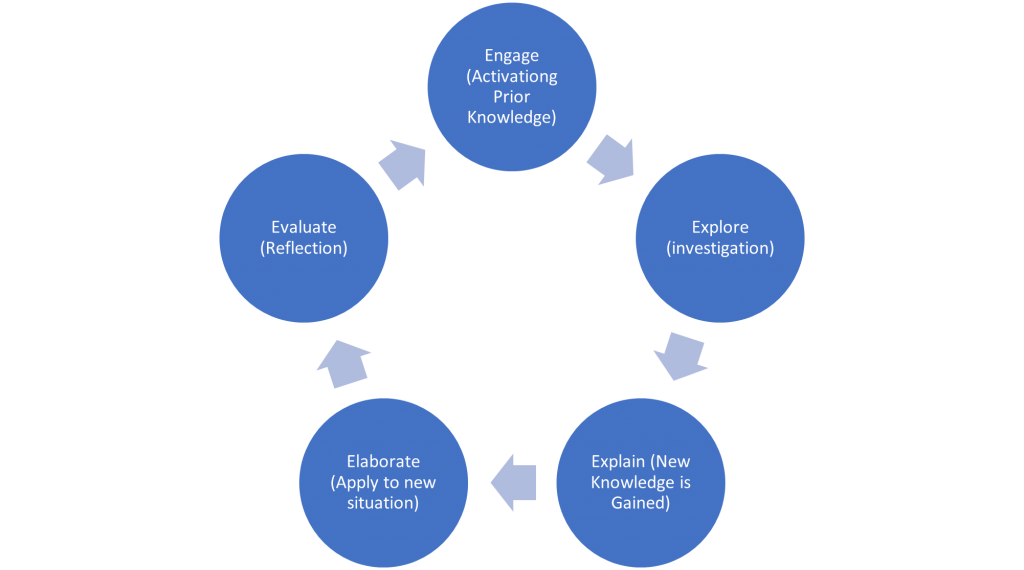

So, what does pedagogy need to look like in the online model? The key is a focus on the 5E model (NASA, 2020). The 5E model is a unit design model that allows for meaningful and deep learning. It begins with an engage phase where we pique student interest and pre-assess prior learning. After, students explore and engage in the topic in multiple ways. Next comes the explain phase in which students communicate what they have learned and this is followed with an extend section in which students can use their new knowledge in new situations. Lastly, an evaluation is performed in which both students and teachers determine what they have learned.

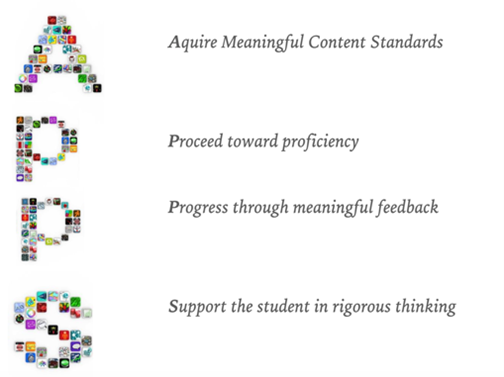

After determining the pedagogical purpose as aligned to learning standards, the next part of the process is choosing the right electronic tool to carry out the purpose. In my world, I use the acronym APPS to make sense of appropriate tools that can be used within the 5E model: they help acquire content standards, they must help students become more proficient, allow students to progress with meaningful feedback, and support thinking. I am also cognizant of COPPA (1998) and CIPA (2000) requirements that restrict certain apps for different age groups or for personal identification information requirements. (You can learn more about this usage of APPS at achievethecore.org). Using the chart below, you can see one conceptualization of how you can connect some APPS to some parts of the 5E model.

| 5E Model | Method of Instruction* | Tool* |

| Engage | Brainstorming | Padlet |

| Explore | Direct Instruction | Edpuzzle |

| Explain | Discussion | BackchannelChat |

| Elaborate | Review | Google Form |

| Evaluate | Assessment | Flippity |

*Many of these methods/tools may appear in multiple areas of the 5E model.

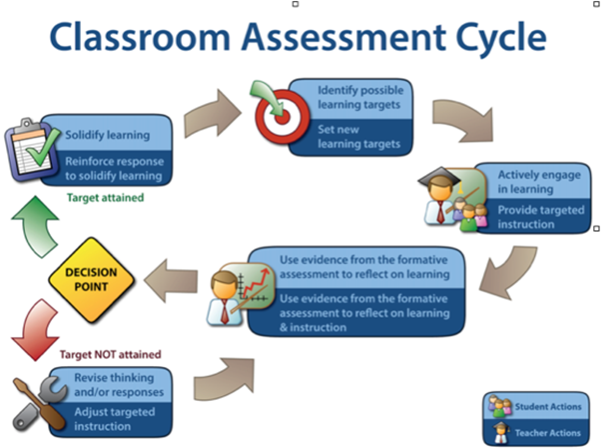

Lastly, teachers must use visible thinking routines as part of a classroom assessment cycle (see the diagram), as we know that strong formative assessment practices make the difference for all learners whether digital or face-to-face (Drost, 2016; Strahan & Rogers, 2012). Visible thinking routines are pedagogical strategies that allow students to observe closely, reason, make connections, process their learning, and ultimately support the transfer of knowledge (Ritchart, Church & Morrison, 2011).

Harvard’s Project Zero defines these routines as effective tools for helping students learn material regardless of the mode of instruction, virtual or face-to-face. By using these routines, teachers create engagement and independence to allow students to have deeper understanding on a wide range of topics. (You experienced one of these routines at the start of this article: Notice & Wonder). See this website for examples of all of the different routines possible. This matrix here shows some examples of the routines as well.

While students are engaging in thinking, teachers must be making instructional adjustments by making moves in formative assessment (Duckor & Holmberg, 2017). Moves in formative assessment are the behaviors that teachers do when they are informally gathering information to make instructional adjustments. As Duckor and Holmberg have described, there are seven moves that teachers need to think about: tagging, bouncing, probing, pausing, priming, binning, and posing. These actions can happen in any direction and connect instruction to assessment.

| 5E Model | Method of Instruction* | Tool* |

| Engage | Brainstorming | Padlet |

| Explore | Direct Instruction | Edpuzzle |

| Explain | Discussion | BackchannelChat |

| Elaborate | Review | Google Form |

| Evaluate | Assessment | Flippity |

Now that we know the principles, let’s apply these principles to our model Google classroom to show why students can learn when elearning is pedagogically structured in this manner.

Looking at our model Google classroom, you’ll see a pre-assessment that is the engage section of the 5E model. The pre-assessment is a padlet where students share things about the planets. Padlet is a brainstorming webspace where you can embed videos, have discussions, and post information on a given topic. Here’s how to create one. However, it’s not enough to simply have students post a thought. The teacher must make students’ thinking visible to capitalize on the formative assessment process. In this case, why not couple the padlet with a Circle of Viewpoint routine in which students choose a perspective and describe the issue from a perspective such as a researcher or a parent or the president. With this approach, the teacher can then bounce, tag, and bin to make instructional adjustments and decisions.

Another example you’ll see in the model classroom, is a discussion using backchannel chat as part of the explain stage. Backchannel chat is a similar tool to the chat feature of a zoom or google meet (learn how to create it here), but can be used asynchronously when students are watching or engaging with something else (think like the comment feature in Facebook). In our model classroom, the teacher had a discussion where students were engaged in sharing out the various things related to the planets and showed a video to capture some keep concepts. However, in the model classroom the teacher just didn’t stop there and had students complete a visible thinking routine, called the headline routine where students create a headline that captures the important ideas or aspects of the discussion. This allowed the teacher to tag, bounce, probe, and bin to make instructional adjustments for students.

A final example is when the teacher evaluates using a flippity escape room. Flippity is a website that uses Google spreadsheets to create interactive activities for students (you can learn how to create one here and see an example here). In our model classroom, the teacher used this as an assessment of student learning on the planets, then coupled it with the “I used to think” to “now I think” routine, which allowed students to discuss misconceptions on the planets. This allowed the teacher to bounce, probe, pause, bin, and pose and ultimately improve student achievement.

In my own practice as a teacher administrator, I have seen the power that these practices have in improving student success in the digital classroom. While there are no guarantees these three steps will be the silver bullet to online learning, the research is clear that when teachers engage with visible thinking routines in formative assessment and applications connected to the 5E model of instruction, the chances that students will learn to high levels increases exponentially.

Additional resources

Standards for Online Learning from the International Association for K-12 online learning

Quality Matters rubrics for checking your courses features

5E video lib guide at Kent State University to learn more about effective pedagogical models for synchronous or asynchronous learning

References

Colvin, K. F., Champaign, J., Liu, A., Zhou, Q., Fredericks, C., & Pritchard, D. E. (2014). Learning in an introductory physics MOOC: All cohorts learn equally, including an on-campus class. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 15(4). https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v15i4.1902

Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act of 1998 (COPPA). 15 U.S.C. § 6501 et seq. (1998). <a href=”https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/PLAW-106publ554/pdf/PLAW-106publ554.pdf “>https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/PLAW-106publ554/pdf/PLAW-106publ554.pdf

Children’s Internet Protection Act (CIPA). 20 U.S.C. § 9134 et seq. (2000). <a href=”https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/PLAW-106publ554/pdf/PLAW-106publ554.pdf “>https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/PLAW-106publ554/pdf/PLAW-106publ554.pdf

Drost, B. (2016). 8 digital formative assessment tools to improve motivation. AMLE Magazine, 4(2). http://www.amle.org/BrowsebyTopic/WhatsNew/WNDet.aspx?ArtMID=888&ArticleID=675

NASA. (2020). The 5E instructional model. https://nasaeclips.arc.nasa.gov/teachertoolbox/the5e

Ritchhart, R., Church, M., & Morrison, K. (2011). Making thinking visible. Jossey-Bass.

Duckor, B. & Holmberg, C. (2017). Mastering formative assessment moves: 7 high-leverage practices to advance student learning. ASCD.

Strahan, D., & Rogers, C. (2012). Research summary: Formative assessment practices in successful middle level classrooms. http://www.amle.org/BrowsebyTopic/Research/Article/TabId/198/ArtMID/696/ArticleID/108/Formative-Assessment-Practices.aspx

Means, B., Toyama, Y., Murphy, R., Bakia, M. & Jones, K. (2010). Evaluation of evidence-based practices in online learning: A meta-analysis and review of online learning studies. Report prepared for the U.S. Department of Education, Office of Planning, Evaluation and Policy Development. https://www2.ed.gov/rschstat/eval/tech/evidence-based-practices/finalreport.pdf

Bryan R. Drost, Ph.D. is a central office administrator in northeast Ohio. He holds a Ph.D. in Curriculum and Instruction with an emphasis in assessment from Kent State University. He is an Ohio Department of Education Regional Data Lead, a national supervisor for edTPA, former chairperson for NCME’s Standards and Test Use Committee, and one of Ohio’s Core Advocates.

drostbr@gmail.com

Published in AMLE Newsletter, November 2020.