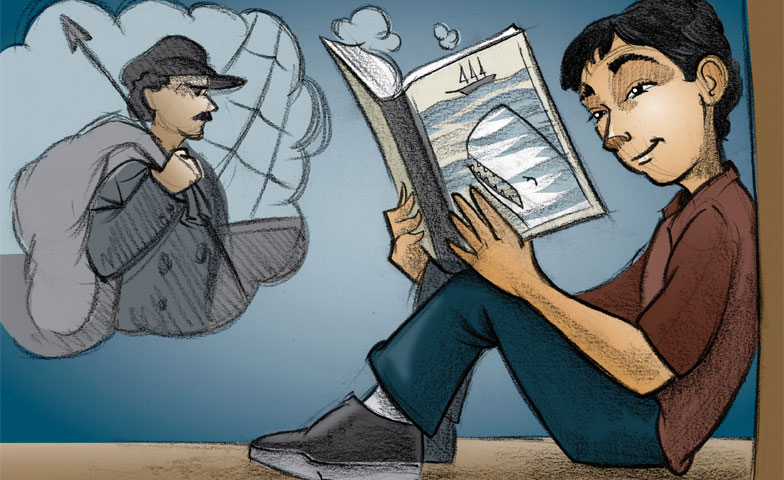

Storytelling brings facts to life and triggers memory and emotion.

Stories stick. They form pathways to memories. They follow the pattern of how we think and learn. They help us to recall, remember, and enjoy. They elicit emotions that burn a memory into our brains.

Why do we tell stories?

To carry on tradition. Important traditions and events are transmitted from one generation to the next through storytelling. The Iliad and Odyssey by Homer and the Analects by Confucius are examples of this oral tradition. Stories can be used to share knowledge, transmit values, and teach lessons. They ensure important ideas and struggles are not forgotten.

To magnify memory. Leo Widrich, in his November 29, 2012, Buffer Social blog (https://blog.bufferapp.com), says, “A story can put your whole brain to work.” When we listen to a story, our brains often envision the action. We see through the lens of our own experiences and form our own emotional attachment.

This visualization process activates the brain in several sensory areas and burns the information into memory through emotion and personal connection.

To construct meaning. Because the story comes to us through the filter of our own experiences and emotions, we connect to it and invest in it. According to Widrich, “A story, if broken down into the simplest form, is a connection of cause and effect. And that is exactly how we think.”

To connect with others. As the storyteller relates the story, the story and the storyteller connect with the audience. The story springs from the storyteller’s personality and energy, evoking emotion and involvement. The listener responds, often with emotion, connecting with the story and the person telling the story.

In the Classroom

Why use storytelling in the classroom? We want students to remember something important. We want them to listen. We want them to learn. For example, in sixth grade social studies in Tennessee, we teach about ancient China. It is tempting to simply name the dynasties and give a range of dates, but storytelling can help students learn more than dates and events. Stories can bring the time period and the people to life.

Here’s an example of how a teacher could use storytelling to teach students about the first emperor of China:

The Story of Qin Shi Huang Di

Qin Shi Huang Di was the first emperor and the leader who united China—but in a most brutal way. He did many good things—he unified the administrative system, made the measurements and the coinage the same, the wagon axles the same length, writing the same throughout the land. He built a vast tomb—the site of the terra cotta soldiers near Xian.

But he also sought to standardize the way people thought. He instituted the doctrine of legalism, which meant everyone was punished in the same way, no matter what status they held in society. The punishments were harsh and there was no recourse; usually, something was cut off.

He hated Confucianism and Daoism, the two major beliefs in China. To stamp out Confucianism and Daoism, in 214 BCE, he burned all the books and buried alive all the scholars who knew the books from memory as a way to eliminate ideas he did not agree with. He also taxed his people and demanded their labor for his huge projects.

Not a nice man.

In China of the Qin Dynasty, Liu Bang was a lowly official whose job it was to transfer prisoners to the work site for the tomb of the emperor, Qin Shi Huang Di.

In 210 BCE, Liu Bang was transporting a group of prisoners and had to spend the night on the road. When he awoke the next day, many of the prisoners had escaped. He knew he would be harshly punished for losing prisoners.

Instead of proceeding on, he rallied the remaining prisoners by telling them that he would free them if they would follow him. Those prisoners formed the core group that started the rebellion against the Qin Dynasty.

After winning and losing and winning battles, Liu Bang became Emperor Gaozu in 202 BCE—the first emperor of the Han Dynasty, which lasted 400 glorious years.

The Elements of Storytelling

This story brings the time period to life. Pictures of terra cotta warriors covering three football fields in the tomb of Qin Shi Huang Di provide visual memories The story gives students a window into the traditions and values of the Chinese, even in the present day.

The pre-eminent storyteller Donald Davis talks about the elements of storytelling in his book, Telling Our Own Stories. He asserts that good stories have four parts: people, place, problem, and progress. The story about China’s first emperor notes who the people are: Qin Shi Huang Di and Liu Bang. The place is ancient China, where they have wagons, building projects, and brutal tactics. The problem is how to survive when you have lost your prisoners—turning a problem into an opportunity. At the end, progress is the advent of the Han Dynasty, considered one of the most stable and enduring in Chinese history.

The story also needs a purpose. In the case of Liu Bang, I want the story to create a hook in the students’ memory on which they can hang knowledge about ancient China. Other reasons for telling stories include illustrating a rule, posing a math problem, setting up an inquiry, setting the stage for reading.

Think about the stories you tell your classes.What are your stories?

- What is the reason for telling this story?

- What are the elements: the people, place, problem and progress?

- What details will you add to paint the picture?

- What action will you describe to help the audience visualize?

Add details to your story that help paint a picture in the mind of the audience. Tell the story with enthusiasm and expression.

In his essay “The Storyteller,” Walter Benjamin says, “The storyteller takes what he tells from experience… And he in turn makes it the experience of those who are listening to the tale.”

| Helpful Storytelling Websites

Storytelling Lesson Plans Advice on the Art of Storytelling Audio of Storytellers National Storytelling Network Collections of Stories |