A teacher’s guide to planning a high-interest, engaging writing project

Three years ago an eighth grade class of mine had a blog project called “Dear Terrorist” where students researched their topics and wrote letters to anyone considering (or participating in) a decision that could harm themselves or others. One girl wrote an open letter to anyone seriously considering suicide. A month later I got an email from a suicidal teen who claimed my student’s letter had got her thinking and stopped her from killing herself! The message brought me to tears and made me think: This is about as authentic and meaningful as writing can get! I often use this example at the beginning of a writing project when I know the culminating goal is to produce a published work for an authentic audience. Though this life and death anecdote is exceptional, my experience in teaching writing through publishing has helped me develop some useful tent poles in leading students to create powerful writing.

Motivation First

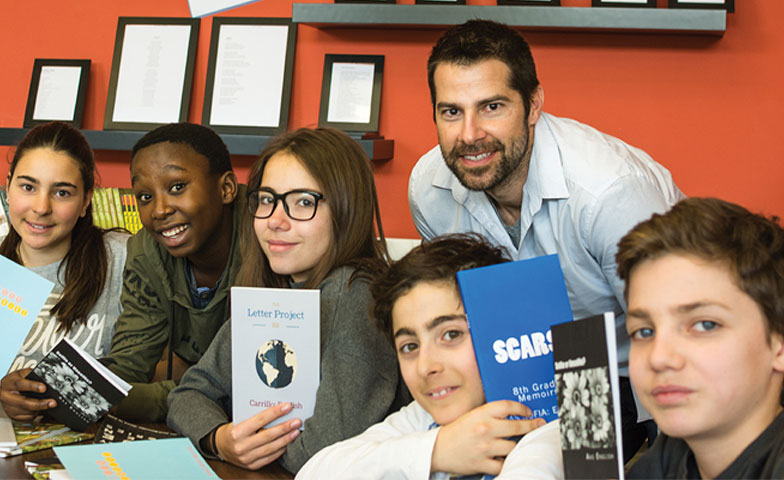

Whether it’s a persuasive letter, essay, memoir, or short story, I emphasize to students that their writing will be published (online and in print) with thousands of potential readers. Perhaps skeptical at first, they believe me when they see prior examples of writing and video projects. Blogs don’t excite them all that much, but knowing that a book will be for sale on Amazon.com usually does. Realizing that they’ll have a printed book and a “real” audience initially sparks their attention, yet students still require a deeper sense of purpose to truly motivate the substance of their writing. Typically, this means the writing topic should both pique their interest and somehow connect to the real world and to the interests of their intended audience whether fiction or non-fiction. For example, my most recent writing project with eighth graders was called The Letter Project. The purpose was to write a persuasive, essay-style letter to someone famous or influential who the student felt could affect positive change if nudged in the right direction. The idea was that if Donald Trump or Miley Cyrus didn’t actually read their letters, then at least an online audience would get the message. Framing the project this way also allowed for considerable student choice and voice as they could pick any figure (from a celebrity icon to the Korean Minister of Education!) and discover their own persuasive style along the way.

Part of what helps motivate or inspire my students is that as their teacher, I too am writing for an audience. This can be replicated by other teachers and done on various levels. By doing the assignment yourself—a common and recommended practice—teachers can better understand the obstacles and pitfalls of the work and use it as a model (ideally open for critique and feedback as well). Thus, the teacher’s audience becomes the student’s and perhaps colleague’s. I usually do this step, and it tends to pay dividends in student learning by showing students that writing is a process and needs continual refinement and by giving students a strong exemplar to work from. I must also admit another advantage that I personally have in the classroom: I have published a young adult novel that my students are familiar with (through me, not any bestseller lists!). Perhaps it helps motivate them if they view me as an authentic writer, but my author aura (if any ever existed) likely fades within the first week of class. In the long run, it’s not my published work but the intrinsic motivating factors that move students forward with enthusiasm for the project.

It Starts with Reading

The best writers seem to agree: Good writing starts with good reading. Thus, in my class, a writing project begins with reading great models in the same genre. If we’re writing short stories, we’ll read and analyze Hemingway, Chekov, and Shirley Jackson; if memoirs, we look at excerpts of Stephen King, Maya Angelou, Malala, and Malcolm X. I also bring out former student work and something I’ve written for the students to critique and practice giving feedback. This portion of the prewriting process could last a few days or a few weeks. During this time, we ask questions about story elements, the author’s voice, intention, audience, theme, characters, organization—all of the Common Core reading standards can be covered. Of course, all language arts teachers hit these standards throughout the year, but the difference is that the students are engaging these standards with a greater sense of purpose within the larger publishing project. They begin to ask: How will reading this make my writing better? Which author will I use as a model for my writing? What will my voice, theme, and organization be? How will it come across to the audience? These questions are not posted on my classroom wall. They emerge organically because all of the students know that their stories will be in a printed book that’s sold on Amazon. It becomes a big deal, and some students even begin to see stars and dream of dollar signs! In most cases, the letter grade (extrinsic motivation) becomes secondary, and their pride in publishing a quality story (intrinsic) becomes the primary goal.

Bad First Drafts and Good Feedback

It’s difficult to write and perhaps even harder to share your writing with a group of peers. So there has to be a protocol for giving feedback. I recommend dedicating a full class period to discussing bad first drafts. I begin with a warm up asking “What is difficult about writing?” After “pair-sharing,” or however you prefer to spark discussion, we read and discuss Anne Lamott’s Shitty First Drafts. If you teach young or sheltered kids, this brief excerpt can be photocopied and censored, but it usually initiates great conversations and reinforces the idea that good writing is crafted through revision and editing, not some mysterious inherent talent. Lamott’s mindset gives students the courage to write and the idea that their first drafts will improve; they just need to stop thinking about it and write!

After students have had time to write their first draft, the writing workshops begin. Based on a common workshop seating arrangement, we move the desks into a large circle so all the students are facing each other. To relieve any tension or stress that students may have in sharing their work, I make anonymity an option, where I (or other volunteers) can read the work of other students. But before anyone starts sharing, I try to establish what Ron Berger calls the “Culture of Critique.” I explain that writers don’t want just any feedback; they want specific, quality feedback. While I encourage starting off with a positive comment, I clarify that saying “Good story, I liked it” might momentarily boost the writer’s ego, but is not very helpful. On the other hand, commenting that a writing piece was “boring” or “sucked” isn’t a critique; it’s rude and hurtful. The emphasis is on giving helpful and specific feedback, which is what all writers want and need to improve. Then the class watches six minutes of video that has become akin to the Gospel in my classroom: “Critique and Feedback, The Story of Austin’s Butterfly.” Something about watching adorable second graders give quality feedback and commentary on student work gets middle and high schoolers to buy into the value of this critique method. It doesn’t hurt that Austin’s final draft turns out so remarkable! Ultimately, students see the value of quality feedback and are ready to critique knowing that the end goal is to create excellent, publishable writing. Student participation in the workshop increases not only because of authentic interest in the project, but also because they are familiar with the oral language and presentation strands of the Common Core standards and know that everything we do in class addresses these. Whole-class peer critique goes from being a dreaded and uncomfortable idea to a purposeful and valued part of the process.

The Peer Editing Funnel

Early in my teaching career, my mentor English teacher once told me that he never read a student’s first draft. Flat out refused. I laughed, but he wasn’t joking. He explained the funnel: workshop editing, peer editing, and gallery editing. The whole-class workshop editing helps get the big picture kinks out by sparking reflective questions that apply to all writers: Is the piece clear? Does it make sense? What is the theme? The intention? Is it effective? What’s it missing? What needs to be cut? It might take two full class periods to get through every student, but keeping it down to five pieces of feedback per story and having students share only their first page makes it manageable and time efficient. The second round should be familiar to all English and humanities teachers: peer editing and revision. Students are given partners and they must closely check their peer’s writing with a checklist and give detailed feedback. The last round of group editing is the gallery walk. Students print out their writing and post it on the wall. The class is instructed to pick a story to scan for final edits and quick fixes, then they rotate when cued. During the entire filtering process, I make sure to check in with each student individually or through commenting or suggesting changes on their shared Google doc. By the end of it all, students are usually impressed with how much their writing has improved through revision and editing—and most of it they’ve done through effective peer collaboration.

Early Finishers = Publishing Team

All teachers appreciate their self-starting, over-achieving students, but what do you do with them when they’ve finished light years ahead of everyone else? In this kind of writing project, they are assigned a leadership role in the publishing process. As part of the publishing team, they can become the chief editor, an editing team member, formatter, or cover designer. Perhaps they can even take on the role of event manager or lead marketer for a school library unveiling, book sharing event, or student exhibition. Once roles are allocated, I make sure that a few essentials are understood. First, a master Google Doc must be created for all the students to paste their final written work and for the editing team to scan as copy editors. Google Docs is an excellent tool for this task. Second, students in charge of design and formatting must acquaint themselves with the chosen online publishing platform like CreateSpace, Lulu, or Blurb, and watch related tutorials. Third, if students are keen on getting their books some real exposure, marketing teams can be formed to research and make a social media plan or plan local promotional events. By this phase, there is typically such a sense of purpose and an “authentic job” for each student that the project runs itself, and I can troubleshoot and help the struggling students with greater ease as we wrap it all up.

Conclusions

Aside from being authentic, this kind of writing project hits almost all the other education field buzzwords—differentiated instruction, peer collaboration, inquiry-based learning, project-based learning—while covering nearly all of the Common Core standards.

Students seem to genuinely enjoy collaborating and come to understand the value of editing. I won’t pretend that every student ends up loving the writing process, but they definitely walk away respecting it, and have learned new strategies along the way. Lastly, I have described some of my favorite writing project plans, but there are many different options and websites that feature a long list of teachers’ favorite authentic writing projects. It’s amazing how much intrinsic motivation and inspiration comes to students who know that their work will be published online, printed, and ultimately reach an audience outside their school.

| Reference

4 of the Best Online Print-on-Demand Book Publishers How to Use Social Media to Market Your Book |