Even the most experienced educators find teaching to be a challenge. The flexibility required to solve unexpected issues; the immediacy of meeting the needs of each individual student; staying current with changing curriculum, technology, and content; and developing relationships with each child makes the profession exciting yet difficult. Swiftly shifting to an online curriculum in the midst of a pandemic does not make educating America’s youth any less stressful! While some teachers are well-versed in current technological trends, not every teacher feels confident implementing these tools and resources, especially with little to no training and during a short period of time. Despite the challenge, educators can meet the needs of students by focusing on social and emotional needs, teacher clarity, and timely feedback.

Students First

Focusing on school connectedness is often a way in which educators and administrators can help students feel cared for and supported, which reduces many health risks and increases a student’s ability to thrive. According to one study, youth who felt connected at school and at home were “found to be as much as 66% less likely to experience health risk behaviors related to sexual health, substance use, violence, and mental health in adulthood” (Steiner, Sheremenko, Lesesne, Dittus, Sieving, Ethier, 2019). The possibility of remote learning or socially distanced in-person instruction raises the question of how to create a supportive school environment when classroom discourse, inschool programming, and extracurricular activities are greatly reduced.

Without prioritizing student well-being, students will not be able to focus and engage with the planned activities, and no learning will occur. To combat this issue, it is crucial that teachers create and implement a tool that fosters healthy student-teacher relationships. According to John Hattie, “without students’ sense that there is a reasonable degree of ‘control’, sense of safety to learn, and sense of respect and fairness that learning is going to take place, there is little chance that much positive is going to occur” (Hattie, 2012). To create this environment in a virtual format or in a socially-distanced atmosphere, teachers can create a survey to check in daily with students.

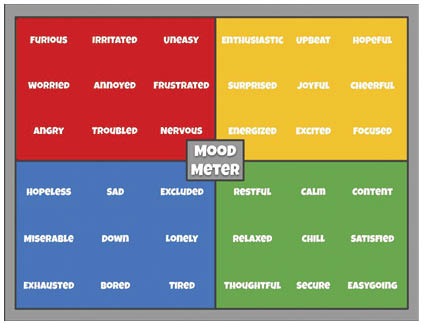

When creating a survey it is important to select a platform that will be easy for students to access on their own so they are more likely to engage. When I created a quick survey to implement with my students while remote learning during the coronavirus pandemic, I developed a short Google form, and posted in my Google classroom accounts for my students to easily access. To incorporate a research-based social and emotional learning approach in my survey, I based my form on the RULER Mood Meter developed at Yale University. Figure 1 shows the mood meter I developed based on Yale University’s tool. I placed this image at the top of my survey with directions for students to select one term that describes how they were feeling that day. After selecting one of the terms, students explained why they chose that word and then indicated whether they’d like a follow up with me.

If so, I sent a personalized email to students with a compliment and asked if there was anything else they’d like to discuss. By keeping the survey short and providing an opportunity for a follow up conversation, I was able to keep in contact with students, ensure that they were doing well, and support them as much as possible.

Make it Clear

It can be difficult for students to engage on their own if they feel they can’t be successful or don’t have the support they need to experience that success. This is where teacher clarity comes into play. According to John Hattie, “The more transparent the teacher makes the learning goals, the more likely the student is to engage in the work needed to meet the goal. Also, the more the student is aware of the criteria for success, the more the student can see and appreciate the specific actions that are needed to attain these criteria” (Hattie, 2012). Now more than ever, students need to know why they are learning what they are, how they can learn it, and what they are to know and be able to do.

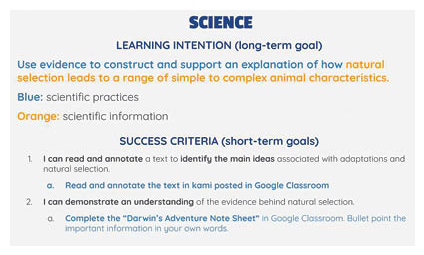

To establish clarity, teachers need to provide their students with learning intentions and success criteria. Good learning intentions, “are those that make clear to the students the type or level of performance that they need to attain, so that they understand where and when to invest energies, strategies, and thinking, and where they are positioned along the trajectory towards successful learning” (Hattie, 2012). These statements are viewed as the long-term targets that are directly pulled from standards and can be written in student-friendly language. Success criteria on the other hand, can be viewed as short-term goals and as a checklist for students to determine when they have accomplished what they are supposed to. When establishing success criteria, it is important to remember that “we must not make the mistake of making success criteria relate merely to completing the activity or a lesson having been engaging and enjoyable; instead, the major role is to get the students engaged in and enjoying the challenge of learning” (Hattie, 2012). Students need to understand the importance of the learning journey and be able to envision themselvesp meeting the learning intention.

Figure 2 is an example of a Google slide displaying the learning intention and success criteria for a science lesson. While remote learning, each daily assignment started with a slide containing the learning intention and success criteria. Making these accessible and achievable ensured that students would view them and feel that they could reach the intended goal.

Timely Feedback

Students should have access to a plethora of formative assessments where they receive information about their progress toward an intended goal. These should not count toward the final course grade, as they are meant to update students on their current knowledge and skill acquisition trajectory. Students who are on the path to mastery of the learning intention should be notified that they are making adequate progress, and students who need additional support should be provided that as well. John Hattie argues that to make feedback effective, “teachers must have a good understanding of where the students are, and where they are meant to be—and the more transparent they make this status for the students, the more students can help to get themselves from the points at which they are to the success points, and thus enjoy the fruits of feedback” (Hattie, 2012). While all teachers would agree that feedback is an important aspect of learning, it is often diminished due to the lack of time available, particularly in a remote environment. To address this concern, a rubric should be created for assessments so teachers can provide more timely feedback in an efficient manner.

The rubric should be available for students to see, and it should be standards-based so the provided feedback focuses on students’ learning and current understanding as opposed to a specific score. This way, students are more likely to pay attention to the statements and understand if they need to make changes or if they are on the path to mastery. I like to include a category that extends learning for students so instruction can be differentiated, and students who wish to attempt learning beyond mastery can do so. By utilizing formative assessments and feedback as a tool for improvement, students have opportunities to make changes before completing a graded summative assessment.

Concluding Thoughts

Despite the obvious challenges of remote learning and socially distanced in-person instruction, teachers have the ability to make the best of an incredibly difficult situation. Creating clarity by providing detailed learning intentions and success criteria ensures that students can see themselves succeeding. Providing timely and efficient feedback through standards-based rubrics guarantees that students understand where they are in their learning and where they are in relation to the learning intention. This also allows them to make the necessary changes before demonstrating their knowledge for a grade on a summative assessment. Of course, all of this can only be accomplished if we first tend to our students’ most basic needs and continue to create and foster strong relationships. While teaching through a pandemic isn’t easy, educators still have the power to help their students.

References

Hattie, J. (2012). Visible learning for teachers. Routledge.

Steiner, R. J., Sheremenko, G., Lesesne, C., Dittus, P.J., Sieving, R.E., & Ethier, K.A. (2019). Adolescent connectedness and adult health outcomes. Pediatrics, 144(1). https://doi.org/10.1542/ peds.2018-3766

Nicholas J. Leonardi is a seventh grade science teacher at Mannheim Middle School, Melrose Park, Illinois.

![]() leonardin@d83.org

leonardin@d83.org

Published in AMLE Magazine, October 2020.