“So what IS a passing grade?”

That question at a recent team assembly of sixth graders, teachers, and support staff brought the discussion to a complete halt. The inquiry by a young lady with braids, braces, and Hello Kitty backpack was not meant to be humorous or disrespectful, but rather an honest plea by a learner trying to make sense of the transition between elementary school expectations and middle level grading standards.

Some background:

In Hawaii’s public elementary schools, student achievement of the state standards is assessed through proficiency levels: Meets with Excellence (ME), Meets Proficiency (MP), Developing Proficiency (DP), and Well Below Proficiency (WB). The middle schools and high schools use traditional letter grades, A–F. Although the state’s assessment system is uniform in most aspects, the jump between elementary and middle level can be overwhelming for students trying to navigate the waters of early adolescence as well as school structures.

Lost in Translation

Back to our team assembly:

Our team meeting was scheduled near the beginning of the new school year, after the first round of progress reports were handed out. The team brought their group of learners together to discuss how to use student planners and how to meet deadlines—all in an attempt to boost completion levels and address some of the issues illuminated on the progress report.

Many of the sixth graders acknowledged the move between elementary and middle school was somewhat confusing, but they also said they were excited for the new adventure. When teachers asked if they were comfortable with schedules and classes, most hands went up. When asked if they were using their student planners on a regular basis to keep track of assignments and due dates, again many students raised their hands. However, when asked how many of them understood and were accustomed to receiving A–F grades, only three hands emerged from the crowd.

It was then that the inquisitive young lady asked the show-stopping question. None of the adults had considered that a translation between standards-based report card grades and traditional scoring practices would be necessary.

Most students understand traditional letter grading systems, yet these sixth graders were unable to grasp the gravity of earning a D or the impact a zero has on grades. Until they entered middle school, these students were part of a system that assessed their levels of proficiency toward meeting standards. They did not need to pass a class or earn credits to be promoted to the next grade. Receiving a D or F had no meaning for them now, since the closest interpretation was a DP (Developing Proficiency) and was never a cause for alarm.

On the other hand, the sixth grade teachers were concerned about the general progress of the students and the large percentage of students with Ds at the first progress check point.

In a standards-based system, learners become accustomed to different stages of progress toward achieving the standards. The idea of “failing” or “not passing” is a foreign concept. As teachers help students bridge their understanding of elementary grading practices with those at the middle level, we need to examine the elements of our assessment to ensure our methods are fair and clear to all learners.

Personal Connections

As middle grades educators struggling to find equity in assessment while honoring the strengths of our learners, we (authors) began crafting a translation guide for students in middle school that can help bridge achievement levels with reporting mechanisms. Based on the work of Ken O’Connor, Carol Ann Tomlinson, Jay McTighe, and Bob Marzano, we revised our own practices in reporting student assessment to be more student-friendly and less ambiguous.

One of the most prominent inconsistencies and misconceptions about the 100% grading scale is that it is fair and balanced. The famous quote, “What’s popular is not always right, and what’s right is not always popular,” summarizes what has happened in most gradebooks for a century.

Based on the 100% system, an A typically ranges between 90% and 100%; a B equates to 80% to 89%; a C falls between 70% and 79%; a D squeaks by with 60% to 69%; and an F represents 59% and below. When students are rated solely on this scale, there is little or no recovering for a student who receives a zero (F) on one assignment.

For example: A student receiving percentage grades for 5 assignments (B = 88%, B = 80%, B = 84%, B = 83% F = 0%) would receive a D (67%) based on the average of all grades. The approach favors a mean average over the mode of achievement by the learner. This type of evaluation tends to be more punitive and does not allow for a growth model or standards-achievement.

If the scores were to represent a growth model where the learner started out low, with a struggling score of 0 for a missing assignment, then slowing improved and earned 88, 80, 84, and 83, an argument could be made that achievement has been made toward the expectations set forth, and perhaps a B- would be the more appropriate grade. Why should students be penalized for a low grade or single missing assignment in the beginning of a semester when they have shown improvement over the course of the term?

Likewise, if the scores were reversed and the student’s performance decreased—88, 84, 83, 80, and 0—then perhaps a C would accurately reflect the student’s academic level. Either way, does the learner truly deserve a D?

When letter grades are aligned with even increments, or single point values, the playing field is leveled for learners. If the same student was evaluated on a 4-point scale where 4 points are given to an A, 3 points for a B, 2 points for a C, 1 point for a D, and 0 points for an F, the student would receive a C as the average overall grade (Ex: 3 + 3 + 3 + 3 + 0 = 12/5 = a 2.4 mean score). Although this mean also provides a norm score for the learner, the individual grades are in equal increments and don’t give more weight to one assignment. Additionally, this format can utilize a growth model to determine if the lowest score was early or late in the grading term to be factored into an overall assessment.

Assessment vs. Grading

For holistic views of assessment, letter grades can’t always serve as the best measurement tool for learners or parents interested in understanding the proficiency levels, thus many teachers will use checkmarks or narrative feedback to inform performance status for their students.

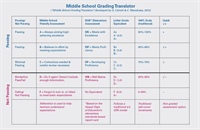

We, too, have been faced with myriad assessment techniques, strategies, and measurement scales that reflect learner progress at different stages. The chart below is one form of translation that we developed to help students and parents better understand how grades are interpreted while also offering equity between the grading levels.

Assessment and grading are not synonymous, but they do go hand-in-hand when it comes to reporting accomplishments and achievements within learning environments. And, although varying philosophies, practices, and systems will continue to evolve as research supports more holistic approaches to evaluation, the least we can do as educators is offer explanations, in the form of translation, to learners seeking answers to the question “What’s passing?”

Sandy Cameli teaches at Konawaena Middle School in Kaelakekua, Hawaii. scamelis@aol.com

Colleen Masukawa, teaches at Konawaena Middle School in Kealakekua, Hawaii. comasuka@aol.com

Published in AMLE Magazine, August 2013.